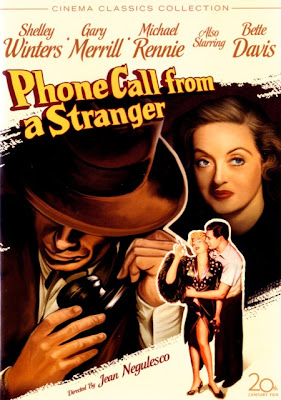

PHONE CALL FROM A STRANGER (2oth Century-Fox 1952) Fox Home Video

Star-billing in ensemble acting is always a problem.

In Jean Negulesco’s Phone Call from A Stranger (1952) – a uncanny

amalgam of noir-styling, conventional melodrama and a touch of screwball comedy

- it becomes downright confusing. Case in point: Shelly Winters is given above

the title credit, even though Gary Merrill has infinitely more screen time. The

script by Nunnally Johnson and I.A.R. Wylie is a tedious mishmash of clichés

and uncertainties with a few brief nuggets of hidden surprise that seem to come

out of nowhere. And the roster includes Bette Davis – having officially entered

her emeritus years, as little more than token ‘star power’ – decidedly on the wan,

as a bedridden housewife. The story concerns David L. Trask (Merrill) an

attorney running away from his home life after he discovers his wife, Jane

(Helen Westcott) has been unfaithful. Telephoning Jane from the airport, David

next buys his ticket under an assumed name. He is ‘picked up’ by lonely

ex-actress/former stripper, Bianca Carr (Shelley Winters) while waiting for

their flight in the terminal, and thereafter, also befriends two other

passengers; traveling salesman, Edmund Hoke (Keenan Wynn) and Dr. Robert

Fortness (Michael Rennie).

The flight takes off under a terrible storm and is

grounded in Vegas overnight. Dr. Fortness confesses a deep dark family secret

to David, whom he is hoping will be able to provide some much-needed legal

counsel. It seems, one night not so very long ago, the good doctor departed a

fashionable party with fellow colleague, Dr. Tim Brooks (Hugh Beaumont) on

route to treat a patient at a nearby hospital. Unfortunately, David’s cockiness

and the influence of alcohol contributed to a head-on collision where Brooks

and all of the passengers in the other vehicle were killed instantly. Lying in

hospital, Fortness tells presiding physician, Dr. Luther Fletcher (Harry

Cheshire) it was Brooks, not he who was driving the car. Fortness’ story is

backed by his dutiful wife, Claire (Beatrice Straight) even though she knows

the truth about the accident. The secret eventually tears Fortness’ family

apart.

Meanwhile, inside the airport terminal, Edmund is

proudly passing around a picture of his wife, Marie (Bette Davis). *Aside: the

photo is actually an airbrushed image with Davis’ face pasted onto the body of

a bathing beauty pin-up. Bianca jokingly tells Edmund he is far too lucky to

have Marie as his wife. Fortness agrees. For both Fortness and Bianca, Edmund

is mis-perceived as boorish, grating and nonsensical. However, David finds

Edmund – if not enlightening – then, at least amusing. With weather conditions

all clear, their plane takes off the next morning only to suffer ice build-up

on its engine and wings. It crashes, killing all but three on board. David is

the only member of his troop to survive and spends the rest of the movie’s run

time reluctantly contacting the family members of Dr. Fortness, Edmund and

Bianca to relay their final hours and provide closure and solace to each

family. In Fortness’ case, David is able to reunite Claire – who had become

estranged from her husband - with their embittered son, Jerry (Ted Donaldson).

In Edmund’s circumstance, David learns Marie has been paralyzed for many years

following an ill-fated elopement with her lover. This, Edmund forgave.

The most peculiar of all reconciliations, played out

in flashback like a bad screwball moment ripped from another film, involves

David’s brief interaction with nightclub proprietor, Sallie Carr (Evelyn

Varden) and Bianca’s estranged husband, Mike (Craig Stevens). Possessive

mother-in-law, Sallie hated Bianca’s independence – fabricating a persona for

her to read more like that of the heartless vixen. Sensing Sallie’s relish in

demonizing Bianca, David fabricates a bit of his own wish-fulfillment about

Bianca’s audition for Rodgers and Hammerstein; thereby deflating Sallie’s claim,

her daughter-in-law was a ‘no good’ useless failure in life. The picture concludes with David’s sobering

gratefulness to be alive; a reminder that, in life, there are no guarantees and

the best one can hope for is longevity of a kind, even if happiness itself is neither

bountiful nor forthcoming.

As film entertainment, Phone Call from A Stranger

is acutely convoluted. Nunnally Johnson and I. A. R. Wylie’s screenplay suffers

from too many half-baked ideas that never meld into one cohesive narrative.

Merrill does his usual laconic ‘world weary’ loner routine with bittersweet,

and, thoroughly aloof disenchantment. He never seems terribly engaged, but rather

trudges from one plot point to the next with an ‘Am I there yet?’

mentality that, at times, is rather oppressive. 1952 was hardly a golden year

for Merrill and Davis – having fallen in love on the set of the Oscar-winning, All

About Eve (1950) and shortly thereafter to wed, the couple quickly

discovered they had little in common outside their mutual interests as actors.

Davis suggested Jean Negulesco to direct, if she could also indulge in the cameo

as Marie Hoke. Johnson had originally hoped to coax Lauren Bacall into playing Binky Gay – a part, the actress turned down flat. The movie is also

noteworthy for the big-screen debut of the marvelous Beatrice Straight – a sensation

on Broadway. In hindsight, it is the slickness of the exercise that intrudes

upon its entertainment value; the pieces fitting too succinctly together, so as

to reveal the mechanics in the exercise. Rather than appearing organic to the various tales it is attempting to tell, the Johnson/Wylie screenplay reveals the

inner-workings of its construction, increasingly to become a stilted, and

stuffy exercise in maudlin melodrama. Bette Davis is wasted here. After her

turn in All About Eve, Davis’ acceptance of the part of Marie (a part

and performance any actress could have played blindfolded) has to be one of the all-time

curiosities in American cinema. Shelley Winters is a bit long in the tooth to play

the tart with a proverbial heart of gold, though she mostly pulls it off with

her usual aplomb. Wynn overplays his hand with a painful example of ham acting.

In the end, the characters do not gel the way they should. Ditto for the plot –

running through a series of truncated vignettes. The results are therefore

mediocre at best.

Fox Home Video provides a beautiful DVD transfer. The

B&W image exhibits exceptional tonality in its gray scale. Blacks are deep

and solid. Whites are nearly pristine. Contrast levels are perfectly balanced.

Age-related artifacts are rare and do not distract. The audio is mono as

originally recorded and presented at an adequate listening level. Extras are

limited to an interactive press book and lobby and stills gallery. Bottom line:

forgettable pastiche to stars who ought to have known better than to partake of

it. Pass, and be very glad that you did!

FILM RATING (out of 5 - 5 being the best)

1.5

VIDEO/AUDIO

4

EXTRAS

2

Comments