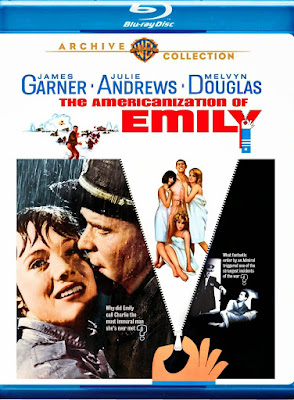

THE AMERICANIZATION OF EMILY: Blu-ray (MGM 1964) Warner Archive Collection

Most movies

are the undiluted vision of their director; a visual artist’s personal imprint

that becomes more apparent upon repeat viewings of their body of work. On

occasion, however, the focus has shifted from director to producer, perhaps

nowhere more distinctly than in those movies made by David O. Selznick, so

clearly and obviously reflecting his thoughts, his morality and his ideals; the

director assigned to helm these productions, a mere minion, expected to fulfill

Selznick’s edicts. Rarely, however, in the history of American cinema has the

writer been given such consideration, leeway, or even accolades as a movie’s

acknowledged auteur; unless, of course, he also happens to be its director, as

say, a Joseph L. Mankiewicz or Preston Sturges. Hence, The Americanizaton of Emily (1964) is all the more extraordinary

and unique. For although the movie is amply realized by its director, Arthur

Hiller, the essence, nee – the spirit - of the piece is undeniably dictated by

screenwriter, Paddy Chayefsky’s erudite prose. William Bradford Huie’s novel

defines ‘Americanization’ as a sort

of faux prostitution; English girls trading sexual favors to the Yanks in order

to acquire stylish clothes, perfumes, and, lavish outings to fashionable

parties and nightclubs; all of it ultimately culminating in midnight rendezvous

inside the swankier suites of London hotels; the Savoy, Dorchester or

Claridge’s.

In

reconstituting this rather seedy premise, Paddy Chayefsky has superficially

gleaned only Huie’s basic premise and characters. Instead, he has taken an

almost perverse and very esoteric approach to this material; the tale of an

unrepentant coward, slick and devilishly handsome dog-robber, Lt. Cmdr. Charles

Edward Madison (James Garner) and the priggish English widow, Emily Barham

(Julie Andrews) he comes to seduce and eventually care for, becomes a mere

platform on which Chayefsky grafts an even more sublime social commentary about

the ever-lasting psychological perils of war; its deification of heroes and

heroism as insidious to the perpetuation of mankind’s self-destruction as any

misperceived notions of valor. The genius in Chayefsky’s writing is that it

never come across as a weighty tome - stagnated or preachy - but miraculously

retains a self-reflexive quality, easily disseminated to the audience with razor-backed

honesty. Chayefsky’s characters are far more astute, articulate and able to

philosophize and debate a point of interest, plumbing it to fascinating depths.

And yet none of these characters ever slips into overbearing academia or tedium

in their quest for the truth. Many authors and playwrights have walked this

tightrope. Maxwell Anderson immediately comes to mind. But few have been more

stealthily secure in their clever-clever expositions than Paddy Chayefsky. The

true artistry in his exercise becomes educational almost by accident. The

lesson is taught, but Chayefsky is never obviously the teacher. Indeed,

Chayefsky once clarified in an interview that “our purpose is to entertain. We fill up their leisure. If we also

happen to give the audience something to think about then we have achieved what

is called artistry…and that’s gravy. That’s bonus.”

In retrospect,

The Americanization of Emily remains

an embarrassment of such ‘bonuses’; an unexpected melodrama – deadly serious at

its core, yet wrapped inside an anti-war social critique approached with even more

wicked distraction by way of a thoroughly scathing romantic comedy. Chayevsky’s

wit, his superior intellect and his ability to expound such lofty platitudes

while making them seem more casual conversation, fit for the salon or a playful

parlor game between old friends or lovers; this is the kernel of genius of his

artistry. For although the characters that populate The Americanization of Emily deconstruct and articulate

exceptionally well thought out arguments in order to illustrate both the pro

and con, and, with Chayefsky’s own opinion clearly on the side of restraint,

though arguably, never appeasement, these nuggets of morality and humanity

never unhinge the discussion into wordy byplay. Instead, we are compelled to

listen to his almost rhapsodic theorizing; the conflict between man and woman inventively

plied and exploited as a counterpoint to the warring of nations; the solemnity

in the art of mechanized warfare made to reflect this more intimate contest.

The term ‘highbrow’ is often incorrectly

referenced to mark this chasm between the common collective understanding

(a.k.a. popular opinion) and pure intellectual thought (nee, debate). But

Chayefsky’s prose manage the seemingly impossible; to transfix his audience

with deeper ideas and ideals, their interpretation seeming effortlessly more

easily digestible. Chayefsky always says

what he means and means exactly what he says. Such personalization and

personification of the larger issues at stake, rendered down to their most

basic equation – two people in love – never talks down to the audience; the

eloquence loftier and more resilient than the conflict itself and food for

thought once the houselights have come up.

At the time of its release, The

Americanization of Emily was neither well-received nor critically acclaimed;

if for nothing else, then for Julie Andrews’ miraculous departure from

squeaky-clean and blissfully virginal nuns and nannies. As the title character,

Andrews is given the exceptionally plum role of a widow who, having lost her

husband at Tobruk, and briefly succumbed to the madness of casual liaisons with

many men to drown her sorrow, has somehow managed to slip into a sexual

reformation, morphing into a rather priggish spinster to whom all men – though

particularly American soldiers - now seem an anathema to her newfound

moralizing sense of self. Emily’s resolve is repeatedly tested by her obvious

and growing attraction to Charlie Madison; his chipping away at her faux ‘high-minded

principles with amorous contempt, impeding her ability merely to love and be

loved in return.

Yet Charlie

begins both his admonishment and his assessment of Emily thus, with a very real

condemnation of the war itself: “You

American haters bore me to tears. I've dealt with Europeans all my life…I've

had Germans and Italians tell me how politically ingenuous we are, and perhaps

so. But we haven't managed a Hitler or a Mussolini yet. I've had Frenchmen call

me a savage because I only took half an hour for lunch. Hell, Ms. Barham, the

only reason the French take two hours for lunch is because the service in their

restaurants is lousy. The most tedious of the lot are you British. We crass

Americans didn't introduce war into your little island. This war, Ms. Barham to

which we Americans are so insensitive, is the result of 2,000 years of European

greed, barbarism, superstition, and stupidity. Don't blame it on our Coca-cola

bottles. Europe was a going brothel long before we came to town.”

This, of

course, has the opposite effect intended. For only a few hours later, Charlie

will discover Emily patiently waiting in his bedroom to be served and serviced.

The burgeoning affair gets off to a very rocky start and intermittently

progresses, while Chayefsky’s narrative briefly entertains the approaching

D-Day invasion on the windswept and very bloody beaches of Normandy. The

premise is more necessarily complicated by Emily’s mum (the sublime, Joyce

Grenfell); who has slipped a cog after the brutal death of both her husband,

killed in the blitz, and son – one of many casualties in the war; choosing to

live her days in an indeterminate past where each is still very much alive and

apt to come home at any moment.

Emily

encourages Charlie to play along with this emotionless charade, and briefly, he

does exactly as she wishes, before delving into yet another tirade about the futility

of war. The effect of his admonishment is not immediately felt, for Chayefsky

has gilded the lily of his social critique in a wicked patina of glib repartee;

something of a mild amusement for both mother and daughter. “War isn't hell at all,” Charlie tells

Mrs. Barham, “It is man at his best; the

highest morality he's capable of. It's not war that's insane, you see. It's the

morality of it. It's not greed or ambition that makes war. It's goodness. Wars

are always fought for the best of reasons: for liberation or manifest destiny.

Always against tyranny and always in the interest of humanity. So far this war,

we've managed to butcher some ten million humans in the interest of humanity.

Next war it seems we'll have to destroy all of man in order to preserve his

damn dignity. It's not war that's unnatural to us. It's virtue. As long as

valor remains a virtue, we shall have soldiers. So, I preach cowardice. Through

cowardice, we shall all be saved.”

Charlie’s

critique is both amusing yet frank. But the playful mood of this tea time

garden party quickly sours when Charlie permits himself the luxury to criticize

Emily’s mother for her nascent pride that continues to hold the balance of her

incredible sorrow and imminent joys in a perpetual state of limbo. “I don’t trust people who make bitter

reflections about war, Mrs. Barham,” Charlie tells her plainly, “It’s always

the generals with the bloodiest war records who shout what a hell it is. It’s

always the war widows who lead the Memorial Day parade. We shall never win wars

by blaming them on ministers and generals or war-mongering imperialists or all

the other banal bogies. It’s the rest of us who build statues to those generals

and name boulevards after those ministers; the rest of us who make heroes of

our dead and shrines of our battlefields. We wear our widow’s weed like nuns,

Mrs. Barham, and perpetuate war by exalting the sacrifice.”

“My brother died at Anzio; an everyday soldier’s death

– no special heroism involved. They buried whatever pieces they found of him.

But my mother insists he died a brave death and pretends to be very proud. You

see, now my other brother can’t wait to reach enlistment age. It may be

ministers and generals who blunder us into wars…but the least the rest of us

can do is to resist honoring the institution. What has my mother got for

pretending bravery was admirable? She’s under constant sedation and terrified

she may wake up one morning and find her last son has run off to be brave? I

don’t think I was rude or unkind before, do you, Mrs. Barham?” In fact,

Charlie has paid the widow Barham a great kindness; one that stirs her back to

reality and its bitter thrashings of truth, at last favored over the great lie.

The other

narrative thread as yet not discussed involves Charlie’s superior officer,

Admiral William Jessup (Melvyn Douglas) who, after suffering a queer breakdown,

insists the first dead American on Omaha Beach must be a sailor. Jessup’s

declaration is rather startling and, in fact, paid very little mind by Charlie

or his fellow officers, Lt. Cmdr. Paul 'Bus' Cummings (James Coburn) or Admiral

Thomas Healy (Edward Binns). Nevertheless, the die has been cast. In the wake

of Jessup’s reoccurring departures from reality, Bus falls victim to the

valorization of war, establishing Jessup’s camera corp. of one – Charlie – who

will document the invasion for posterity’s sake and very likely be killed in

his efforts. Bus assures Charlie the likelihood of invasion is virtually slim

to nonexistent; a comfort Charlie confides to Emily who has by now fallen madly

in love with him but cannot bring herself to abide his cowardice. Or perhaps

the real disillusionment is yet to follow.

For as Charlie astutely points out

during their farewell in a torrential downpour at the airport, “I don't want to know what's good, or bad,

or true. I let God worry about the truth. I just want to know the momentary

fact about things. Life isn't good, or bad, or true. It's merely factual, it's

sensual, it's alive. My idea of living sensual facts are you, a home, a

country, a world, a universe - in that order. I want to know what I am, not

what I should be. The fact is I’m a coward. I’ve never met anyone who wasn’t.

You’re the most terrified woman I’ve ever met. You’re even scared to get

married.”

“Oh sure, you married him three days before he went to

Africa. Thank God he never came back. You’re forever falling in love with men

on their last nights of furlough. That’s about the limit of your commitments –

a night, a day, a month. You prefer lovers to husbands, hotels to a home. You’d

rather grieve than live. Come off it Emily. The only immoral thing you have

against me is that I’m alive. Well, you’re a good woman. You’ve done the

morally right thing. God save us all from people who do the morally right

thing. It’s the rest of us who get broken in half. You’re a bitch.”

Charlie flies

off, feeling secure he and Bus will have missed their connecting flight and

therefore be too late to engage in the D-Day invasion. Regrettably, fate has

dealt a more cruel hand. For the ill winds and rain pelting Emily and Charlie’s

during their brittle farewell have also delayed the Allied plans for invasion

by a full day, providing more than ample time for Charlie and Bus to hit the

beach running. Charlie refuses to comply and is physically dragged to the beach

and held there at gunpoint by Bus, now seemingly having succumbed to Jessup’s

delusions of grandeur. Realizing what

a fool she has been, Emily is powerless to tell Charlie how she really feels; she

wants the things he wants – though chiefly, to belong to a man who can be more

than a distant and deified memory, resting comfortably snug in a silver frame

on her mantel piece. Thankfully, Charlie survives his ordeal. He is mildly

wounded and taken to be patched up, finding Emily waiting for him on the other

side; all beguilement with the war and its heroes set aside. Charlie is the

only man for Emily now – his own blunder into heroism a confirmation of his

earlier edict: that through cowardice mankind shall be saved.

The Americanization of Emily is an

extraordinary movie about war and the strange bedfellows it breeds. While other anti-war movies take themselves

and their message far too seriously, Paddy Chayefsky’s critique places tongue

firmly in cheek and, as a result, makes a far more prophetic statement about

valor through irony than perhaps would ever be possible in a more grimly

mounted melodrama. Both Julie Andrews and James Garner give decisive

performances in their respective careers; each going largely unnoticed at the

time of the film’s release. Arguably, The

Americanization of Emily plays far better today as a sobering social

critique; the evolution of our own present cultural cynicism more in tune with

Chayefsky’s brutally funny situations and very acidic wit. There are too few

comedies about the advent of global conflict, perhaps because to poke fun at

its absurdities and willful chaos seems to disgrace the very nature of valor

for which only families that have lost a loved one to war can fully comprehend.

Yet the purpose of Chayefsky’s critique is neither to insult nor diminish the

impact of that loss of life or even to callously dismiss and make light of bravery;

but rather to point to the outcome – the loss itself – as a wholly unnecessary

byproduct of a very flawed human endeavor; namely- the miserably misguided

ambitions of war.

While that ‘other dark comedy’ about conflict - M*A*S*H –

plays as grand farce in the face of imminent peril, a sort of bastardization of

wartime precepts, offering a total escape from the grimness, The Americanization of Emily is

well-grounded with an overriding sense of doom and languor dangling over the

heads of our darling Em’ and her ne’er do well lover. Chayefsky neither shies

away nor exorcises the demons that lay beneath his very buoyant and frequently

extremely funny social critique: an exceptional gift to American cinema and one

for which Paddy Chayefsky’s contributions were virtually all but overlooked at

the time. But The Americanization of

Emily is bar none a superior example of

‘entertainment’ meets ‘the message

picture’: an amalgam by design, it tells a good story, but ultimately,

teaches us so very much more.

Here is a

Blu-ray release from the Warner Archive to get very excited about. I only have

one genuine complaint and one minor quibble with this Blu-ray. First, the

complaint; that 'Emily's' hi-def debut wasn’t given the proper fanfare. Everyone

should be aware this film is out in hi-def and be ready to snatch it up in a

heartbeat. This is a near ‘reference quality’ disc, beautifully showcasing

Philip Lathrop's Oscar-nominated cinematography. Prepare to be impressed. The

gray scale exhibits superb tonality; blacks - deep and solid; grays and whites

finely allocated with subtle shadings that bring even the minutest details in

hair, clothing and faces to life as never before. An accurately rendered

pattern of natural grain exists. Now, for the quibble: the brief (very

sporadic) intrusion of video noise. It just comes and goes, seemingly at

random, not terribly distracting but present nonetheless. Again, its’ very minor

and does not intrude – much – on this otherwise fantastic film-like

presentation. The movie’s inserts of actual stock footage are much softer in

focus and grainer – as they have been shot under less than perfectly controlled

conditions – nee, reality. They look about as good as they ever have or ever

will, but they do not align themselves with the rest of the image quality. This

is, of course, as it should be.

The Americanization of Emily sports a

lossless DTS 2.0 mono track which remains something of a curiosity, given that

the movie is listed as originally being released in both mono and stereo. The

track herein has perceptible stereo separation in Johnny Mandel’s score.

Dialogue and most effects are center channel based, but I also detected minor

separation in the left and right channels, particularly during the sequence

where Emily and Charlie say their bitter farewells in the pouring rain. As

before we get Arthur Hiller’s audio commentary; incorrectly advertises as

featuring Drew Casper on the DVD back jacket, but correctly advertised as

Hiller on the Blu-ray. Bottom line: The

Americanization of Emily comes very highly recommended. It deserves to be

seen and this Blu-ray presentation is definitely the way to see it!

FILM RATING (out of 5 - 5 being the best)

5+

VIDEO/AUDIO

4.5

EXTRAS

1

Comments